|

Rumours have been buzzing around the corridors of Toronto's City Hall. It appears that the mayor is considering a proposal to host a World's Fair in 2015.

So why has Toronto been so unlucky? With the global economy pressuring large cities to build ever-expanding convention centres, it would seem that international events would be a dime a dozen. Quite the opposite is true. Trade shows may be on the rise but the number of mega scale events have been declining over the past twenty years. The BIE has limited the number of Universal Expositions to twice a decade. And after some spectacular failures, most notably the 1984 Louisiana Exposition, the BIE has been hesitant to sanction smaller specialized World Fairs to every city that signs the paperwork. At the same time, there are many more cities around the world that have grown to a size where they feel they can support a major international event. Add to the mix all the developing nations that have become industrialized and politically stable over the last few decades -- all of which have bought into the idea that "world class" status can be obtained instantly with an Olympic Games or World's Fair hosted in their cities. The competition has increased tenfold to host world class events.

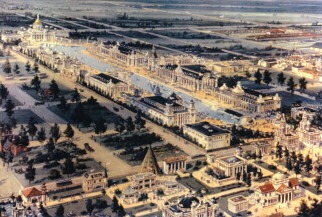

Between the two World Wars, the modern World's Fair came into its own. People no longer flocked to see the innovations of the world's industrial nations but the innovations at work in the fair itself. Corporate pavilions took over the art of selling the latest scientific wonders while national and international pavilions began to sell politics and culture. This revolution of hard-sell political propaganda perhaps reached its zenith with the two monolithic pavilions built by Russia and the United States across the canal at Expo 67.

With a bid that was described as "spectacular," Toronto was ready for the challenge to host Expo 2000. The Millennium world's fair would have been the first in North America since Expo 86 and one of the largest expositions in history. But in East Germany's last act as a self-governing republic they voted in favour of Hannover, and with that, Toronto lost the bid by one vote. Before and after that, Toronto tried for the Summer Olympic Games and a smaller World's Fair -- and lost. But that doesn't keep Toronto from trying. After all, how many times can you roll snake eyes? Once again a future bid may be in the works. Recently, the city of Toronto's website has placed on display a Feasibility Study on the topic. The report favours hosting a World's Fair, outlining financial and social benefits that would last decades. If Toronto hosts a World's Fair in 2015 it would most likely be situated all or in part along the waterfront Port lands. The site is excellently suited for the task. Centrally located close to the heart of the city, the Port lands consist of several islands criss-crossed by canals. Part of the area has already been transformed into parkland. The map below shows the dual site recommended in the Staff Report. Highlighted in pink are areas outside the gate dedicated to transportation, parking and other external activities associated with the fair. The areas highlighted in blue would be the lands dedicated to exhibition space.

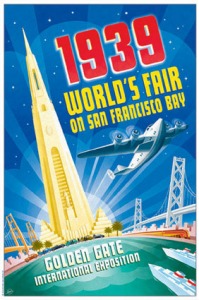

Port Lands development has been put on hold for many years due to prior Olympic and World's Fair bids and many Torontonians are saying enough is enough. Another bid would delay development a further 10 years and even if Toronto hosts Expo 2015 it would take at minimum another decade until post fair construction could start. Plans for a film studio may be halted with another bid. The other hurdle with the site plan is an existing airport which would have to vacate an island well before the lease runs out. Other "world class" cities are already considering their World's Fair potential for 2015. As it stands now, Toronto may have to compete with a sentimental favourite San Francisco ( which would mark the 100th anniversary of the very popular Pan Pacific World's Fair) and Istanbul (which would be the first World's Fair held in a primarily Muslim country). Moscow, Casablanca, and Buenos Aires are also possible contenders. The bids aren't in and already Toronto appears to have extremely stiff competition. On the flip side, there are the enthusiasts who claim that Toronto can't afford not to host a world class event. Too much has been invested to give up when future economic kickbacks are far too great and long-lasting. Vancouver, for example, is still experiencing a post Expo economic boom in the travel and retail sectors almost twenty years after the 1986 World's Fair. Seattle, Brisbane and other such cities that have hosted a fair claim the same. There is much more at stake than civic pride. Despite the potential benefits, garnering public support through another bid process could be difficult. Torontonians have banded together and rallied three times only to be met with disappointment. Just how much public enthusiasm can be once again generated is in question. Do Torontonians have the willingness to try again or is there city-wide bid burnout. That remains to be seen. Toronto's Expo 2015 would be the second Universal fair and the third World's Fair for Canada. Although Calgary set its sights on Expo 2005 and lost, no other Canadian city to date has aspirations to host a World's Fair in 2015. Will it be Toronto's turn? Perhaps the fourth bid will be the charm. Only time will tell. * * * * *

|

This

isn't the first time Toronto has tried to host a major world event. In

the last decade alone the city has spent millions of dollars submitting

bids to both the International Olympic Committee (IOC) and the Bureau

of

International Expositions (BIE). The cards have not been stacked

in Toronto's favour, however. This circle of failed bids has

turned

Toronto into Canada's poster child for lost opportunity. It's a

woeful

tale of one city's hapless efforts to nab that illusive brass ring.

This

isn't the first time Toronto has tried to host a major world event. In

the last decade alone the city has spent millions of dollars submitting

bids to both the International Olympic Committee (IOC) and the Bureau

of

International Expositions (BIE). The cards have not been stacked

in Toronto's favour, however. This circle of failed bids has

turned

Toronto into Canada's poster child for lost opportunity. It's a

woeful

tale of one city's hapless efforts to nab that illusive brass ring.

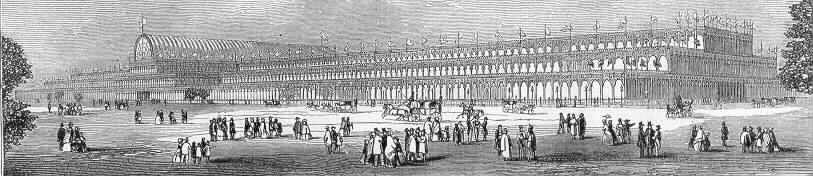

In

the early years after the "Great Exhibition of 1851," World Fairs

ping-ponged

between Paris and London with an occasional volley to New York

City.

That stronghold ended during the dawn of the twentieth century as other

countries with a burgeoning middle class found World's fairs to be a

lucrative

and prestigious investment. The United States alone hosted a

minimum

of three world's fairs a decade throughout most of the twentieth

century.

In

the early years after the "Great Exhibition of 1851," World Fairs

ping-ponged

between Paris and London with an occasional volley to New York

City.

That stronghold ended during the dawn of the twentieth century as other

countries with a burgeoning middle class found World's fairs to be a

lucrative

and prestigious investment. The United States alone hosted a

minimum

of three world's fairs a decade throughout most of the twentieth

century.  The

1980s saw a strong shift in public opinion. With cities across

North

America increasingly suffering from infrastructure and social problems,

it became difficult to persuade the public that the benefits of

hosting

a Worlds Fair outweighed the financial burden. The break-up of

Soviet

Russia and the fall of the Berlin wall decreased the need to sell

political

ideas at home and abroad. And with millions of dollars at stake

in

the bid process alone, the World's Fair slowly died out in North

America.

That didn't stop some cities, however.

The

1980s saw a strong shift in public opinion. With cities across

North

America increasingly suffering from infrastructure and social problems,

it became difficult to persuade the public that the benefits of

hosting

a Worlds Fair outweighed the financial burden. The break-up of

Soviet

Russia and the fall of the Berlin wall decreased the need to sell

political

ideas at home and abroad. And with millions of dollars at stake

in

the bid process alone, the World's Fair slowly died out in North

America.

That didn't stop some cities, however.