| When Skytrain was unveiled to the public just prior to Expo 86, it was an instant hit. The locals began to feel that Vancouver could finally boast that it had the beginnings of a "world class" transit system comparable to other major cities. What many people forgot was that the only thing unique to Skytrain was the technology. Almost a century earlier people were riding the very same route in electric trolley cars. In fact, the lower mainland once had an impressive network of public rail transportation that was the envy of cities across the continent. |

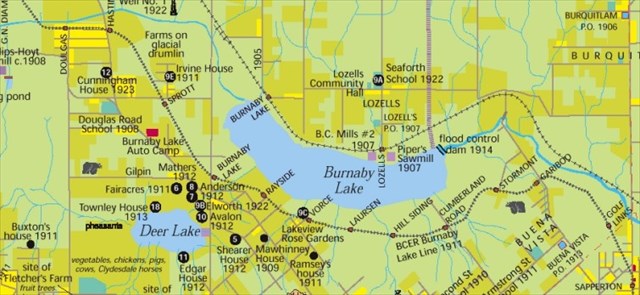

| Vancouver was only five years old when the first trolleys began running between Gastown and New Westminster. Christened the Interurban, the first electric railway line ran down Kingsway. Early travellers taking a trip from one city to the other would have witnessed Burnaby's countryside in a flurry of development. Between the two cities, tracts of forest gave way to clear cuts which in turn were ploughed into farmland and fruit orchards. The rich, beckoned by an easy ride out of the city, built country homes along the lakes. This was the era when Fairacres, Anderson House and Avalon were built around Deer Lake. |  |

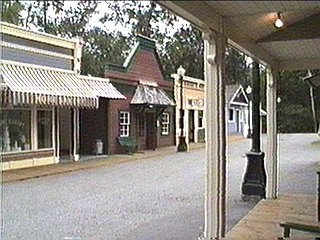

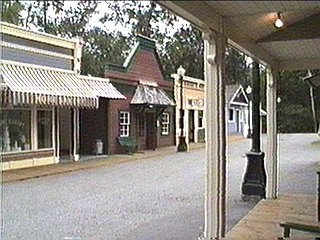

| Quaint town centres formed around several of the Interurban stations. Each station village was unique in some way in order to lure passengers off the the trolley to shop. Although the years have not been kind to the Interurban hubs, you can still find one or two of them along the skytrain route. One such town centre, in the form of several old buildings, is located at the intersection of Imperial and Nelson Streets.

Burnaby Village Museum has lovingly restored the ambience of an Interurban Station community as it would have looked during the Edwardian era. |

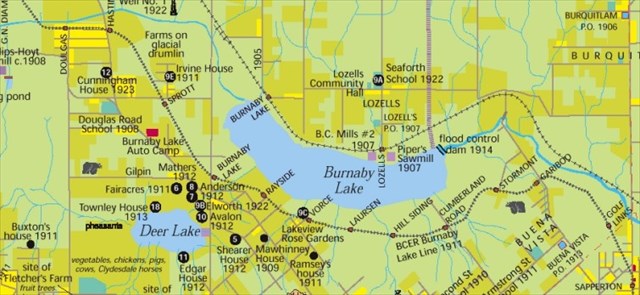

The development spawned by the Interurban was so great the British Columbia Electric Railway Company decided to buy up more land and expand the service. One popular route spread out to Richmond via the Arbutus corridor. But when the Burnaby Lake Line was opened in 1911, the economy slowed to a standstill. The sprawling suburb planned for the south side of Burnaby lake was stalled due to the depression of 1912. Only a few homes were built. Because of this, the Burnaby Lake Line was considered the scenic route and the dark horse of the system. After that, engineers and city planners decided to take a cautious approach and only built new lines where development already existed.

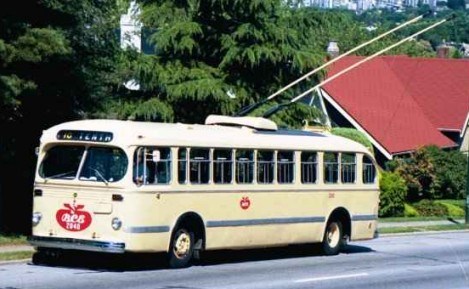

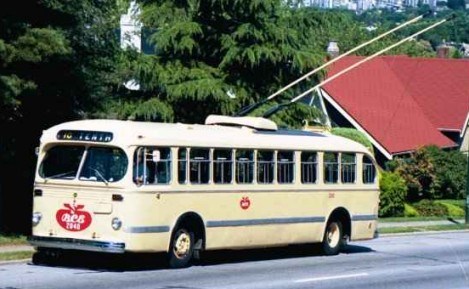

There was another type of depression that halted development in the area. Before flood controls were put in place, the Burnaby Lake lowlands were primarily bog and swamp. Unstable land in the area caused one train to sink -- taking the life of one engineer, several chickens and a goat. A mud slide caused a major derailment along the Brunette River killing 28 men. In an effort to alleviate slumping tracks and sinking trains, some sections of the Burnaby Lake Line were designed to float on a tightly packed bed of wood chips. With the exception of the interurban and suburban routes, much of the trolley system used existing roadways. The increasing popularity of the Automobile throughout the 20th century began to result in a general feeling that trolleys and cars could not co-exist. The most common complaint by motorists concerned the tracks themselves. Automobile wheels often got stuck in the track grooves causing motorists to unwittingly swerve the automobile down the trolley line. Numerous accidents were blamed on this phenomenon. In the 1940s, the cities and municipalities serviced by the electric railway banded together to solve the trolley problem. A modern counterpart that could utilize the existing power source (inexpensive electricity) was needed. The answer came in the form of the trolley bus.

| These busses could be run on roads while using the overhead electric cables originally set up for the rail trolleys. By the early 1950s, trolley buses replaced the electric railway lines. This bus system is is still in use today. Baby Boomers will remember the original electric busses well. |  |

The Burnaby Lake Line ceased operation in the Autumn of 1953. The Kingsway Line followed suit in 1954. The last trolley car in the lower mainland made its final run along the Steveston / Arbutus route in 1958 after 44 years of trouble-free service. Vancouver would not see public rail transit for almost thirty years.

| The Trans Canada Highway, using the same "floating" roadbed design, was built along much of the Burnaby Lake Line's path in 1963. That particular section of the highway virtually floats over the swampland and will rise and fall with changes in the water table. Motorists that commute along the highway daily are aware of its fluidity. During inclement weather cycles, bumps and dips in the pavement will appear and disappear from one week to the next. |

Today there are ten British Columbia Electric Railway trolleys still in existence. Three are operational. For those who would like a taste of what it was like to travel on the electric railway, two of the trolleys have found a new life running between Science World and Granville Island. The Downtown Historic Railway Company hopes to expand the service to Chinatown and Gastown. A third trolley is currently being restored for the Burnaby Village Museum.

| The Kingsway Interurban Line now serves a dual purpose for Skytrain and a linear bike path. The Burnaby Lake Line was a contender when Skytrain's Millennium Line was proposed but the Lougheed Highway route was chosen because an elevated track would be next to impossible to build along the Burnaby Lake lowlands. Several sections of the Burnaby Lake line still exist in varying forms of decay, parts of which have been incorporated into the parks system. Although it remains unused, he Arbutus route is the only trolley line which still has tracks. |  |

| THE CACHE This geocache is located along the last untouched section of the Interurban railbed in Burnaby. The tramline lays in slow decay since the tracks were ripped up in 1956. Viewing the map above, you'll be walking the area between what was once Cariboo and Golf Links stations. Notice that the grade is relatively flat but this was the steepest grade of the Burnaby line -- and the most scenic for passengers in the early 20th century. Note that this is second growth forest and passengers along the Interurban were given spectacular views of the Central Valley strawberry fields and beyond. While strolling down the trail, look towards the ditch (south) side of the trail and you'll see stumps. But these stumps are special. They are what is left of the hydro poles that ran the trolly system. Counting paces between the "stumps" will help find the remains of the poles in the undergrowth. They're evenly spaced. |

The cache placement itself is a typical "Scruffster" hide owing to the fact that there has to be at least one element of adventure. The terrain rating is high for a reason as you will see when you get there. This location is not far from the mudslide that derailed one Interurban street car in the early 20th century. Don't derail too.  The trail system is accessible from many areas including Cariboo Road. However, parking is best at the north end of Sapperton Avenue. I must give the usual cautions. While enjoying the hunt, know your limits. Do not sacrifice your health for a smiley. And please please please, return the cache to its original location. I've often found that the average geocacher's sense of adventure dwindles drastically after they sign the logbook. If you see the cache and know you can't return it. Please don't try to snatch it. It's important that all geocachers after you are able to share the same experience.

Hint: This aint no monorail but you'll still have to cross it and reach.

|