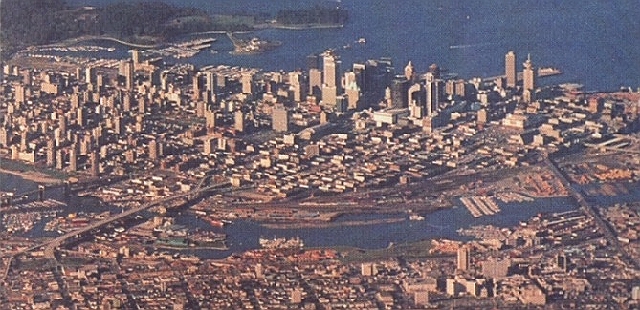

(False Creek and downtown Vancouver in the 1970s)

Expo '86 History

Why did Vancouver want a Worlds Fair?1986 marked Vancouver's 100th anniversary. It was also the centennial of Canada's first transcontinental passenger train to arrive on the shores of the Pacific Ocean. With these important milestones in mind, the government of British Columbia and the city of Vancouver toyed with the idea of hosting a World's Fair. The idea wasn't entirely new.

The first proposals for an international fair date back to the 1920s. But the World's fair of 1936, which would have celebrated Vancouver's 50th birthday, never got off the ground due to economic problems associated with the Great Depression.

The idea of re-establishing a plan for a World's Fair was half-heartedly debated after Seattle's fair in 1962 and Montreal's fair in 1967 but no proposals were viewed to have any realistic merit until 1978. It was on that year, at an impromptu meeting in London's Calvary Club, that two influential members of British Columbia's government first discussed an architect's proposal for Vancouver's centennial celebrations. The proposal included a small international exhibition.

In nearby Washington State, Seattle's fair in 1962 had the distinction of being the only world's fair to make a profit and Spokane hosted a successful World's Fair three years previous. With a stable and strong tourist industry beginning to take hold in Vancouver, the idea of hosting a World's Fair seemed achievable.

The wheels were in motion, but if there was to be a fair, all sectors of the government had to act quickly. A bid to host an international exhibition in 1986 had to be submitted to the BIE no later than 1979. In what was perhaps one of the fastest acts of British Columbia's political history, the plan was approved and a bid to host a Specialized Exhibition was submitted to the Bureau of International Exhibitions within a year.

Planning the Fair

The time between the original bid and the actual event saw many changes to Expo '86's overall plan. However, the theme remained constant throughout the process.

Expo '86 Theme.

The dilemma was to come up with a theme that was, at least in part, unique to the city hosting the fair. During the early planning stages, the one reoccurring theme that kept popping up was transportation.

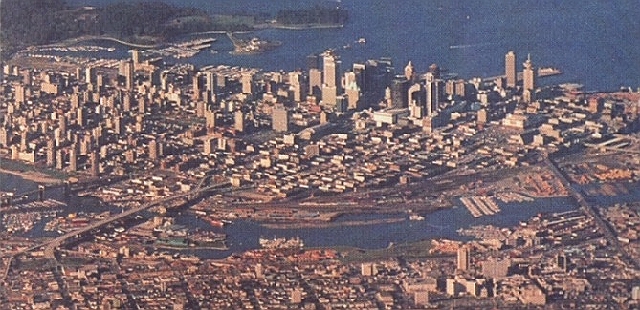

It was clear that the natural geography that gave Vancouver its beauty also made the city a transportation nightmare. In the 1970s Vancouver was suffering from a range of transportation problems due to growth, the popularity of the automobile and the loss of several public systems.

The Inter Urban, a public transit trolley line that linked New Westminster to Vancouver, was long abandoned. Bridges to North Vancouver rendered the city's ferry system obsolete. However, new transit schemes on old themes were being launched at that time. The sea bus system, based on the old ferry routes, became widely popular after it was introduced in the 1970s and in order to ease automobile congestion, the city was eager to establish a modern rapid transit system along the old Inter Urban tram line.

It was also noted that throughout history Vancouver's economic well-being was intrinsically linked to milestones in transportation. Vancouver's very existence was sparked by the building of a transcontinental railroad 100 years earlier, and 100 years before that, the Pacific Northwest was considered one of the most isolated areas of the world. It was one of the last coastlines on the globe to be included on the world map.

So, three hundred years after Captains in tall ships first mapped its remote shores, Vancouver was to transport millions of people into the city for a grand festival of art, culture and history. The fair, christened "Transpo '86," was to be in itself a transportation milestone.

The Site

Originally, the world's fair was to be held on the grounds of the Pacific National Exhibition. The PNE was to receive a facelift, new modern pavilions and a monorail to the downtown core. This idea would sound familiar to the people of Seattle. The original design of Expo 86 was almost a mirror image to the World's fair of 1962.

During this time, Vancouver was negotiating to buy back land on the north shore of False Creek from the Canadian Pacific Railroad. A century of heavy industry turned the area into an eyesore. But the south side of False Creek had successfully been developed into housing communities, parks and a public market during the "city beautiful" movement of the 1970s. The same type of urban renewal project was proposed for the north shore along with a 60,000 seat covered stadium.

(False Creek and downtown Vancouver in the 1970s)

When the Pacific National Exhibition grounds were deemed too small for a World's Fair, the Transpo '86 organizers set their sights elsewhere. The False Creek area was an ideal setting near the downtown core and close to the proposed rapid transit route. Incorporating the rapid transit system into the World's Fair plan was thought to be a convenient way to garner extra funding from the federal government for both projects.Vancouver's city council wasn't receptive to the False Creek Plan. They were looking north to the picture perfect setting seen on many postcards, namely Coal/inner harbour. That area was next door to tourist destinations and the hub of the city. The harbour was also the area where the city council thought legacy structures could best be used afterwards. The hit television show "Love Boat" filmed a season premiere episode on location in Vancouver complete with scenes at the old, dilapidated Balintine Pier where cruise ships docked at the time. To say the least, the TV episode shown around the world was not entirely flattering to Vancouver. So, in the City Council's eyes, a World's Fair had to bring in some permanent structures that would beautify the city. The "wish list" included a large convention centre, a waterfront park and fountain, and of course, a new cruise ship terminal. But the problem with the inner harbour was land availability. In order to host a fair in that area, extensive land fill projects or a compromise on the size of the fair were in order.

In 1980, the Bureau of International Expositions unanimously voted in favour of Transpo '86 and suggested that the False Creek site was the best alternative of all the proposals. The name "Transpo '86" was changed to "Expo '86" to give the fair a universal appeal. Architect Bruno Freschi was hired to design a conceptual model of a World's fair on the False Creek site.

By the early 1980s, several major projects and all levels of government were entwined into the Expo '86 plan. Opposing agendas did not correspond. Cost estimates skyrocketed and land disputes on the proposed rapid transit line erupted. Negotiations over which level of government was obligated to pay for certain projects and potential deficits escalated to such a heated pitch that the Provincial government canceled the World's Fair in 1981. It was a surprise to the public four months later when the Provincial government announced that Expo '86 would go ahead as scheduled and the Federal government agreed not only to build the largest Canada pavilion ever erected but a new cruise ship terminal at Pier BC as well. A lottery was established to help pay for the cost of Expo '86, and a short time later, the first working site model was unveiled to the public:

There was no problem with space on the site, but as the number of international and corporate participants grew, pavilions replaced parklands. Expo planners began to treat the Expo site like a giant jigsaw puzzle in an attempt to keep an aesthetic balance while fitting everyone in.The Module

When hosting a Specialized Exposition, the host country provides indoor exhibition space (if required) for the international participants. Traditionally, this exhibition space has been in the form of large structures shared by many countries. But with ample room on the False Creek site, the Expo '86 architects developed a unique way for the international participants to occupy individual pavilions of their choosing. This gave Expo '86 the feeling of a Universal Exposition while maintaining architectural continuity.

Although the international participants could choose to design their own pavilion, most countries opted to use the less expensive Expo '86 module.

Each module was approximately 2.5 stories high and had the floor space relative to a third of a city block. The design was such that any number of the square modules could be placed together in a variety of shapes. The self-supporting roof design allowed the interior exhibit area to be uninterrupted by pillars.

The participant was only to determine how many modules they wished and which shape they would like the modules placed. It was up to the participant to decorate the structure -- outside and in.

The artist's rendering above shows the 8 modules (2 rows of 4) that made up Japan's pavilion. While many countries opted for elaborate exterior decoration, Japan's designers decided to keep the module's structural integrity exposed.

Why the Module?

Expo 86 was simply the first phase of the largest urban renewal project to take place in North America. It was clear from the beginning that only a few permanent structures would remain after the fair. The module was an inexpensive way to create a large, indoor space. As they were prefabricated, the modules could be set up and removed quickly with a minimum amount of labour or stress to the environment.

The module was also designed to have a high resale value. Although sturdy, the light weight structures could be sold, shipped and easily reassembled to fit most any landscape.

Pavilion Size

In one case, a few countries banded together to share one module. Most countries used one or more modules to create their pavilions. The largest use of the module included:

14 modules -- shared by California, Oregon and Washington State.

11 modules -- Union of Soviet Socialist Republics,

9 modules -- Peoples Republic of China,

8 modules -- Japan

6 modules -- Britain, United States, Italy, France, Australia, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia

5 modules -- Korea, Germany, Czechoslovakia.Leading up to the Fair

International participation is important to a World's fair, but corporate North America, private sponsorship is crucial. Deals were struck with many corporate giants such as General Motors, Coca Cola, Minolta, Kodak, Canadian National, Canadian Pacific, McDonald's, and the Royal Bank of Canada, which all together, pumped millions of dollars into the fair.

Kodak sponsored the nightly fireworks display and the venue for the RCMP Musical Ride. Minolta sponsored the "Space Drop" and General Motors' "Spirit Lodge" was undoubtedly one of the most popular attractions at the fair. The official sponsors did get something out of the deal, however. Only Kodak film could be found on site and if you craved a hamburger at Expo 86 it better have been a McBurger. There was corporate advertising onsite but it was mostly limited to subliminal arty banners.

Offsite, the official sponsors helped advertise the fair to a degree that would not have been realized without them. For years leading up to the fair, CP train engines and airplane tails were painted with the Expo 86 logo. McDonald's drink cups (at least in Canada) and Coca Cola cans sported the Expo 86 logo. So anyone buying a coke, ordering a drink at McDonalds, looking out the window at an airport or stopped at railway tracks would likely have been subjected to some form of Expo 86 advertisement.

It has been argued that the Expo organizers had to sell their proverbial soul to the corporate devil in order to host a fair. Whether the pros outweighed the cons is subject to personal political views.

The Final Hurdle

The construction phase officially ended one month before opening day and 8 million dollars (CAD) under budget. Two weeks before the fair, the site was opened to the construction workers and their families. Although only 12 pavilions were open for the two day trial period, the test run went remarkably well.

Expo Opens

To much fanfare, Prince Charles and Princess Diana officially opened Expo 86 on May 2, 1986. With 54 Nations, 12 Provinces/States, 14 corporate or specialized pavilions and the largest gathering of entertainment Vancouver had ever seen, the party began.

Vancouver had reason to celebrate. Approximately 50% more than the predicted 13.7 people visited the fair. And shattering Vancouver's reputation as a rain soaked city, 130 of the 172 days were dry.

The Legacy

Although it sat dormant for a few years, the British Columbia Pavilion Complex / Plaza of Nations is used for small conventions and is home to several of Vancouver's festivals. The Canada pavilion is now a cruise ship terminal and convention centre. Expo Centre is now the home of Science World.

With a deficit of 311 million dollars (CAD), it was projected that it would have cost much more than that to build the much needed structures (including the infrastructure) from scratch. The industrial neighbourhood on the north shore of False Creek was cleaned and opened for urban housing. Pollution levels in the waters of False creek have dropped to the point that city council has determined that it is not out of the question to open the area for swimming in the future. And with over 22 million visitors to the fair, Vancouver's economy got a much needed boost. Today, Vancouver is one of the world's top travel destinations.

What happened to the site?

After the fair, developers bid on the site. The lease for the entire 175 acres went to Concorde Pacific development team based in Hong Kong. The site has been sectioned off into neighbourhoods -- each with it's own distinct theme and architecture. The 30 year urban housing plan is to be finished in 2016.

As of 2001, approximately two thirds of the expo site has been fully developed into housing, retail and park land.

A photo essay on "Expo: 15 Years Later" can be found in the Miscellany section of this website.